In “Of Fathers and Sons,” Documentarian Talal Derki returns to his native Syria and gains the trust of Abu Osama, a founder of the Al Qaeda-affiliated Al Nusra Front. Believing in an Islamic caliphate, Abu Osama indoctrinates his sons in his beliefs, sending the oldest two, Osama and Ayman, to a military training camp. The brothers have differing reactions to their training, however, with Ayman longing to return to school.

Talal Derki took surprising risks to complete the documentary, the story of 45-year-old Abu Osama, one of the founders of the Syrian Jihadist group al-Nusra, and his young sons. To infiltrate the world of this radical Islamist family, Derki impersonated himself as a believer who wanted to document Osama and his children to further al-Nusra’s militant objectives.

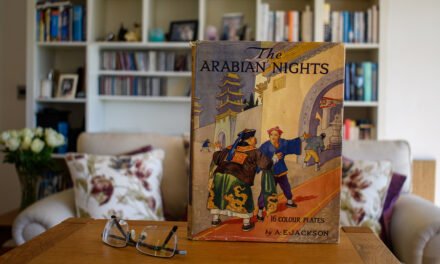

Abu Osama (center), one of the main characters in “Of Fathers and Sons,” surrounded by some of his children. Photo courtesy Basis Berlin Filmproduktion

Young Jihadists in training. Osama, 13, is second from the left. Photo courtesy Basis Berlin Filmproduktion

- Talal Derki: I don’t have that much background in religion so I told them that ‘the light of jihad came to my eyes and you are right and I’m here to learn. At the same time with my camera I can help make [films] for you.

- Q: The allowed you to reveal in intimate detail the influence of a fundamentalist ideology that constitutes one dimension in the chaos of Syria’s Civil War.

- TD: I wanted to penetrate the psychology and the emotions of this war, understand what made people radicalize and what drives them to live under the strict rules of an Islamic state. Although I am an atheist, I prayed with them every day and led the life of a good Muslim to find out what is happening in my country. How can a kid like 10 years old dream of caliphate, instead of having a normal life, playing around or doing some sports? So they are victims in this war.

- Q: What were you feelings about the father in your story?

- TD: He [the father] sends the kid he loves so much, his son he loves so much, he sacrificed him for his ideology. I witnessed the death of a lot of children who were involved in this war. They carried weapons [even though] they could barely hold them because of the weight. In a Muslim society the power of the father authority, the father decides what their kids should be, how to speak, how to behave, where to go, where not to go and what to study. Osama, the boy, if he was the son of anyone here [in the West] he would be an artist. I know how sensitive he was. But because he grew up in this environment, you saw him throw stones in the girls school. You saw him. He lied to his father about praying. He doesn’t pray. A lot of things he doesn’t believe in. But this is the [reality] around him.

- Q: As a younger man you studied film in Greece, an experience that profoundly impacted you view of the world.

- TD: This is when I opened my eyes… This is what made my character. [I] more belong to the Western culture. I’m at artist at the end of the day so I have different values in life.

- Q: Your values as a filmmaker compelled you to do something most documentary directors don’t — focus on a system of belief that is odious to him.

- TD: Filming something you disagree with — not many artists or filmmakers do that. They go to the thing that they have the sympathy with, things they admire. It not only was stressful or difficult [for me], it’s about how can I convince people to watch such a topic… without switching off the TV or leaving the cinema? This was one of the things I worked on all the time to figure out.

- Q: What was the hardest scene in the movie?

- TD: They know that they’re going to die soon and I was filming them with the camera and [to them] I looked like a jihadist with a shaved mustache, wearing the same clothes [as the executioners] and they look at you and they are afraid of you. I really felt broken. I want to go and whisper in their ear that it’s going to be all right or, ‘I will tell the world what’s going on here,’ but I couldn’t [lest it blow his cover]. I wasn’t able to do anything, even to smile to their faces. I was really broken like them.

- Q: Is there any possible resolution to the bloodshed in your country, given the complex dynamics of the situation.

- TD: I’m not optimistic. But I go on this psychological path in the film so people can understand that it’s a legacy of violence. Even every time you bomb a city there will always be people who become a Jihadist [as a result]. They were normal, then they become a Jihadist. So the solution for me is… more intervention in the education system and to end the power of the man authority, fathers, [in Muslim countries].

- Q: How do you break the cycle of violence?

- TD: Even the school teachers should not hit the kids for nothing. I was hit a lot when I was in school. This is also because children are like glass. If one breaks, it’s broken. And the child will not understand. He becomes something we would not wish anyone we love to be like. Also women should get more freedom, they should be more equal in those Muslim countries if we really want the future to be as we wish.

- Q: Your film carries a message to opponents of Islamist ideology…

- TD: [In the film] I reflected what he believes in, his faith, his beliefs. He believes 100-percent in what he’s doing. And this is what I want to show — that they are super-believing. They are not fake. [Americans] should see how this society looks from inside, what circumstances make the people what they are, to understand the keys. If you don’t understand your enemy you cannot defeat him.

- Q: How are you affected by the movie and the experience?

- TD: Most of my dreams are bad. I made the decision. I will not lose my head until the film is finished. They still can hunt you. I have received many online threats.

- Q: When will you go back to Syria?

- TD: I will not go back there. Those two films are enough for me. Maybe in the future after the war, I could find access in a different way. It’s a long war [supporting Muslim women’s rights] between open-mindedness and conservative extremists.